Learning about Culture

Tom Abel( 安天木 ) | 慈濟大學人類發展學系

Dr. Abel

Greetings! My name is Tom Abel (安天木)and I am an evolutionary and ecological anthropologist. In Taiwan, most anthropologists are trained in the humanities. Worldwide probably the majority of anthropologists are also trained in this way, with a broad education in the arts, literature, philosophy, and critical theory. But around the world today there are many anthropologists like me, with training in the sciences, especially biology, medicine, ecology, and evolution. I am fortunate to be at Tzu Chi University, which is home to perhaps the best department for scientific anthropology in the country. Yes, we have outstanding anthropologists trained in the humanities, but we also have specialists in medical anthropology, in genetics, in demography, and we have my specialties, again in evolution and ecology. Of course we are all trained in the fundamental principles and ideas and knowledge that is our inheritance as members of the 'tribe' of anthropology. But we include a different perspective on humanity, one that is more grounded in science. Our department among the many within Taiwan is thus evidence of the beauty of anthropology, the strength of anthropology. Anthropology is the study of humanity, but from many perspectives, both humanistic and scientific.

An Experimental Study of the Production of Culture (provided by Tom Abel)

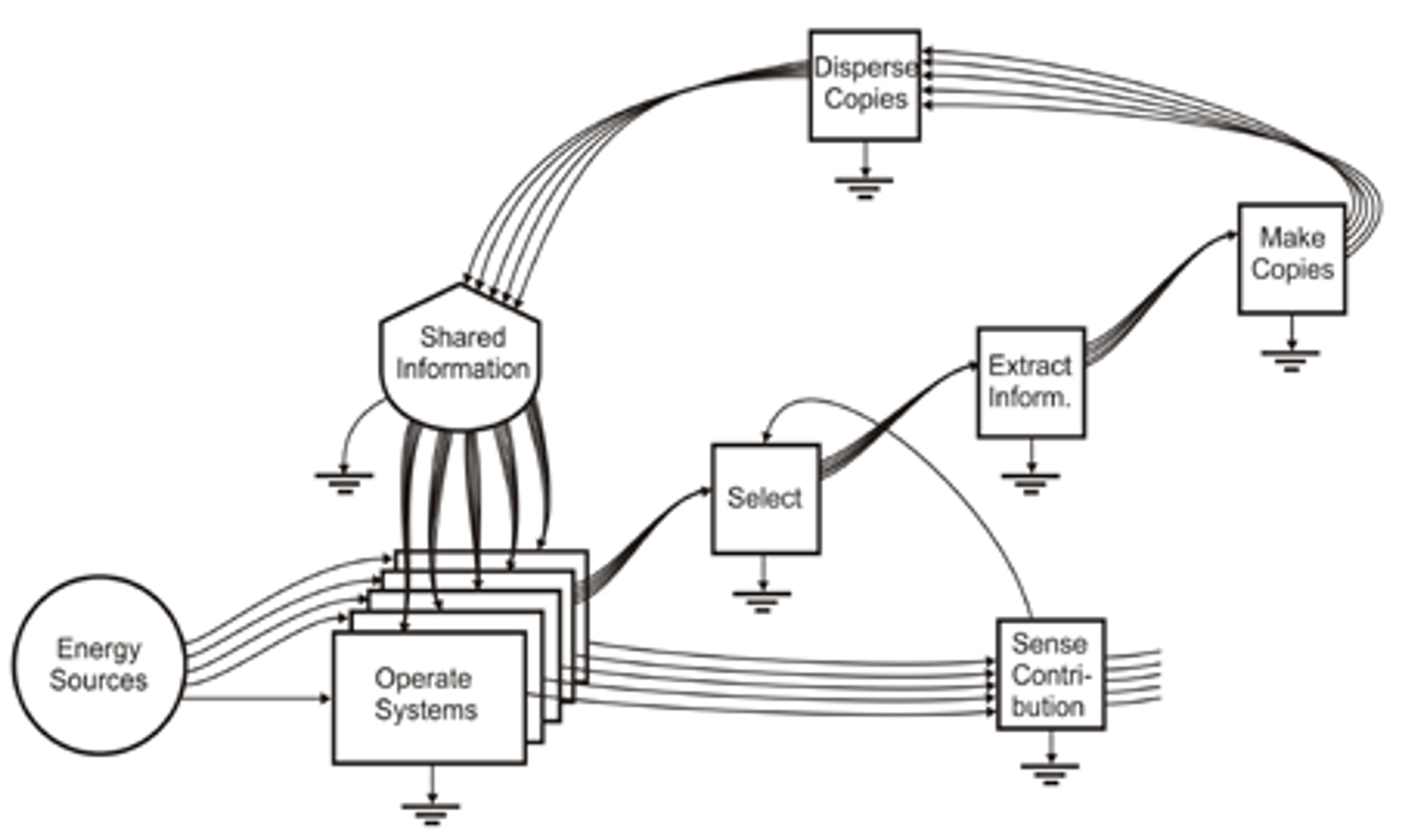

So then, what do I do, what is evolutionary and ecological anthropology? I will give you four examples from four different areas of my research. We can call these (a) cultural evolution, (b) ecosystem anthropology, (c) historical ecology, and (d) sustainability. First, what is culture, and how does it evolve? We could say that culture is the ideas and practices, the performances and rituals, the technologies and strategies, all that give humans our uniqueness and our special powers to survive in every corner of the world, to prosper, and to transform the world. Culture then must be of great value to us. How do we keep those ideas alive, how do we share them with our children, how are they spread more widely across society? These questions are answered today in the study of 'cultural transmission' under the topic of cultural evolution. In this subfield of anthropology. some anthropologists use models from genetics of the 'transmission' of genes in any population of plants or animals, but in their models they replace genes with cultural traits. Instead, I use models from systems ecology of the maintenance 'information', the information of culture.

In my approach, cultural information that is useful must be used. It must be continually shared, discussed, debated, negotiated, some people say 'contested'. It is as if valuable information is 'cycled' endlessly. In that process, of course, it can be modified, enhanced, transformed. But most of the time it is 'lived' within each of us, and used by us for direction, for interpretation, for understanding. I define that process of 'cycling' with an ecological and evolutionary model called the 'information cycle', which came from one of my mentors, the famed systems ecologist H.T. Odum. He used the information cycle mainly to discuss the lifecycles of plants and animals. But he felt that the model was more general and should be applied to people and culture. I have taken on the job of expanding the information cycle model into the realm of culture.

The Information Cycle (HT Odum (1996:223) Environmental Accounting, This material is reproduced with permission of John Wiley & Sons, Inc.)

Student with Log Book (provided by Tom Abel)

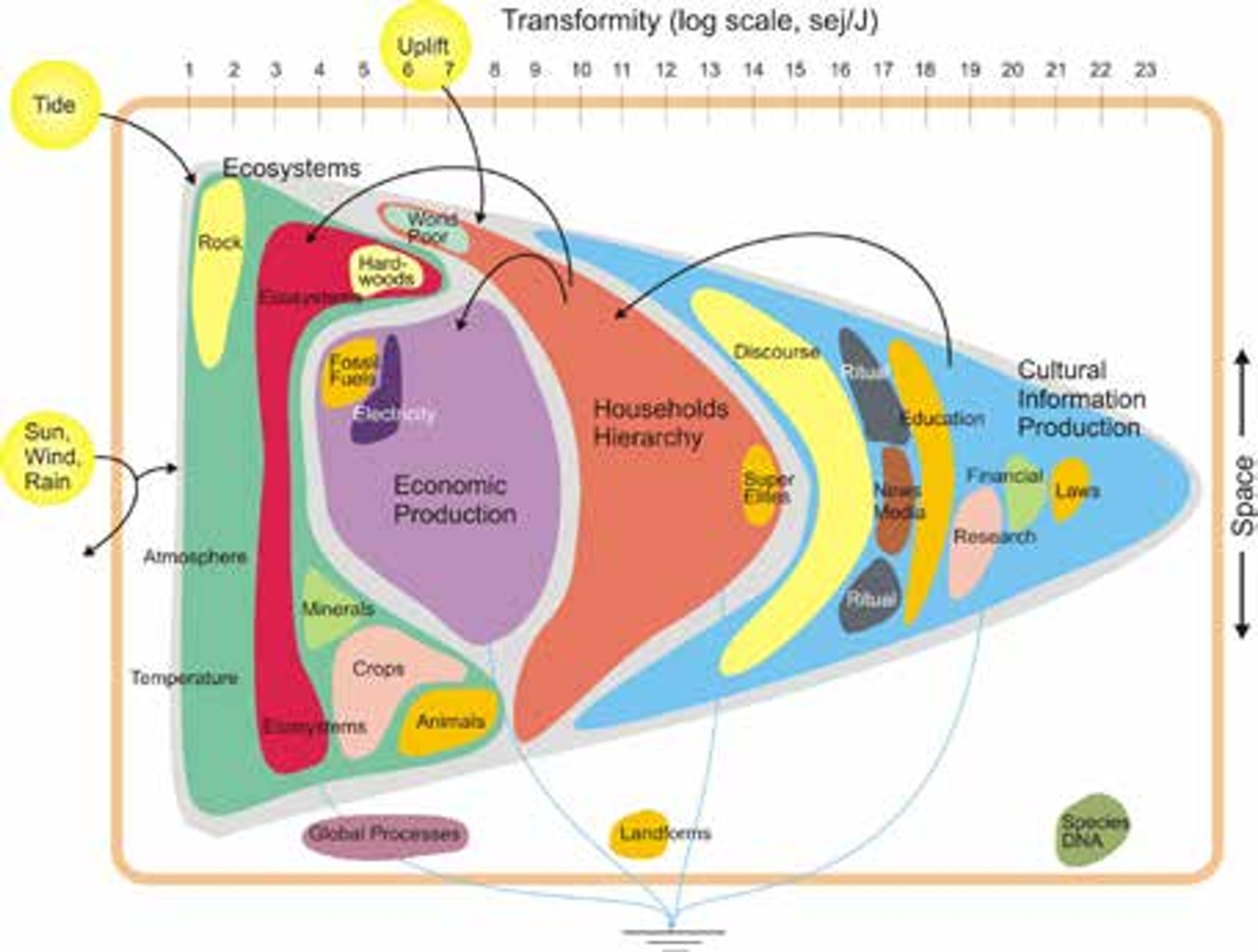

The next topic is ecosystem anthropology. When you look at a place like Hualien County, is there explanation for its form, for the location of villages and towns and cities? Is there explanation for the patterns of nature, of economy, of household. and of culture? Economists often claim to answer these types of questions, at least regarding the shape of an economy. But what of nature, of the structure of home and garden, of the organization and functions of culture (in information cycles), For these questions they have no answer. This is because theirs is not a biological science, not an ecological science, it is instead formal and mathematical. In contrast, the study of ecology is an 'interdisciplinary' physical and biological science. It integrates biology, the Earth sciences. meteorology, oceanography, soils, and others into a single discipline that attempts to answer big questions of organization and function. Why do ecosystems take the shapes that they do, the regular patterns that capture and use sunlight, water, and soil nutrients to produce life in hierarchies of plants and animals?Why invariably do they form into systems that recycle needed nutrients? Why as they develop do they follow regular patterns that we call succession, patterns of increasing complexity and cooperation?

Hualien Human-Ecosystem (provided by Tom Abel)

Farmer Planting Rice (provided by Tom Abel)

In my ecosystems research of Hualien County, I take an ecosystems approach to the study of the total human-ecosystem. I have been studying both the parts and the whole. I have learned about the farming systems that feed us. And I have studied the great industries that dominate the landscape, especially cement and stone production, the paper mill, and the harbor for export and for import. And I have studied the households of Hualien as little ecosystems themselves that need energy and resources in their production of us of parents, children, and elders. For these studies I do not use the tools of economists, but instead use 'ecological economics' that incorporates the understandings of nature that come from ecology.

Next, historical ecology shares with the humanistic study of history a keen interest in discovering the past. What it adds is the science of ecology. Why is that important? Because more often history focuses on human actors, their decisions, their conflicts, and their outcomes as they unfold as one event after another. Historical ecology aims to produce causal explanations of history that are related to our natural environments and the ecological principles that structure them. The objects of ecological studies are ecosystems and they are extremely complex, even more so when they include humans with our culture. Therefore, ecology may seek to predict change, but it is better still at retrodiction, that is explaining change after it has occurred.

When we look at our human past, as in the prehistory of Taiwan and its indigenous populations, we can apply principles of historical ecology to attempt to explain or retrodict the past. From my view, the most intriguing question about Tawain's Austronesian past is, why did they not develop larger and more complex societies. They certainly had productive ecosystems, abundant rainfall, cultigens like taro, and even seed grains in rice and millet. They certainly had time to develop complex societies, considering that the Philippines, for example, or even the Hawaiian Islands, which were invaded by farming Austronesian peoples much later than Taiwan, developed what we call complex chiefdoms. Taiwan, on the other hand, developed only a few simple chiefdoms surrounded by less complex and smaller still local groups or 'tribes'. My approach to explaining this history is to look at the unique ecology and geology of Taiwan, which, before the landscape was dramatically transformed by Han and Japanese colonialists, possessed few stable river bottomlands that were not subject to regular and extreme disruption from typhoon rainfalls. This made irrigationvery difficult to sustain, and it divided the landscape into smaller and often isolated strips between rivers. As any indigenous population around the world, Taiwan 'renjumin' were of course capable of great cultural complexity. Our humanity is what we all share. Our homelands, its potentials, and our place in time we have by chance.

Last, is the world that we live in today sustainable? Is economic development of any kind always a good thing? These questions are asked by researchers like myself who study development impacts and sustainability. We all depend on the ecosystems that support us. Some of them surround us, they are the living patterns of nature within which we live and walk and farm and work and play. But we are also supported by ecosystems that are further away. We depend on the great ocean ecosystems for much of the food we eat. We depend on river and mountain ecosystems to supply us with fresh water. We depend on forests near and far for the capturing of CO₂ in the air, for the wood that we use in countless products, for the wildlife that are hunted by some, and for places of spiritual renewal. While economic development creates employment, gives us products that we desire, and contributes to national financing of valuable public goods like healthcare and education, some economic development can also be harmful for the ecosystems that we depend upon. And it can be harmful to the cultural diversity and integrity that makes Taiwan a unique society. How can economic development be judged, hopefully before it is a reality?

I have conducted two projects related to these questions of economic development and sustainability, and for these I did not pick particularly 'dirty' industries like chemical factories or oil refining. Instead I chose the more extreme cases of economic development that claims to be 'sustainable'. Ecotourism is one example. My research into whale watching ecotourism in Taiwan, and into scuba diving ecotourism on the island of Bonaire in the Caribbean are examples of research that answers those questions, that attempts to judge economic development before or while it is happening. In both of my research projects of ecotourism, I have found that while effort is made to protect the objects of tourism, the whales and dolphins in one case and the reefs and fish in the other case, there was not sufficient concern for the surrounding terrestrial (land) ecosystems and especially for the indigenous human populations that surround the development sites. Better development policy from government agencies can improve that picture.

I hope you have enjoyed this quick tour of research conducted by an evolutionary and ecological anthropologist. Anthropology is a broad discipline with a deep intellectual history. It can accommodate both the scientist and the humanist, and Taiwan anthropology provides many opportunities for building on this tradition.

Whale-Watching Ecotourism (provided by Tom Abel)